I’ve spent quite a bit of time working with Visual Studio’s web performance tests. While it’s easy to use, it’s not as flexible or extensible as Apache JMeter. It’s also impossible to capture a browser session without Visual Studio; it’s format is proprietary.

Visual Studio online supports the use of .har files to drive cloud-based load tests, but again, there are limitations. First, you can only test systems open to the public internet. Also, if you exceed their virtual user quota, you will be billed.

As I’ve spent more time working with the Go (aka Golang) ecosystem, I find myself building out more tools in Go than in C# to improve my own workflow. Jon Oliver offers a similar experience migrating from .NET to Go on his blog.

This article explores my rationale for creating this tool, as well as a code walkthrough, demonstrating some of the Go language features that I find most interesting and useful.

HAR Files

If you’re not familiar with HAR files, I encourage you to read up on the spec.

HAR is the acronym for HTTP ARchive format, which is a JSON-based log of a web browser’s interaction with a website. HAR files can be a requirement for troubleshooting issues specifically for problems related to website performance. For example, slow page load, timeouts when requesting specific URLs, etc.

Since HAR files capture all this detailed information, why not use it to play back the browsing session as a performance testing tool?

To that end, I created Hargo, a .har file based performance test tool, written in Go.

Why write Hargo in Go?

Hargo takes advantage of Go’s built-in concurrency, high performance networking, generous standard library, and cross-platform functionality. I also wanted the non-Microsoft user community to take advantage of a lightweight, useful tool.

What Hargo does

Hargo is a command-line interface tool, deployed as a single executable with no dependencies. It operates in one of several modes:

Fetch

The fetch command downloads all resources references in .har file:

hargo fetch foo.har

This will produce a directory named hargo-fetch-yyyymmddhhmmss containing all assets references by the .har file. This is similar to what you’d see when invoking wget on a particular URL.

Curl

The curl command will output a curl command line for each entry in the .har file.

hargo curl foo.har

Run

The run command executes each HTTP request in .har file:

hargo run foo.har

This is similar to fetch but will not save any output.

Validate

The validate command will report any errors in the format of a .har file.

hargo validate foo.har

HAR file format is defined here: https://w3c.github.io/web-performance/specs/HAR/Overview.html

Dump

Dump prints information about all HTTP requests in .har file

hargo dump foo.har

Load (the fun stuff)

Hargo can act as a load test agent. Given a .har file, hargo can spawn a number of concurrent workers to repeat each HTTP request in order. By default, hargo will spawn 10 workers and run for a duration of 60 seconds.

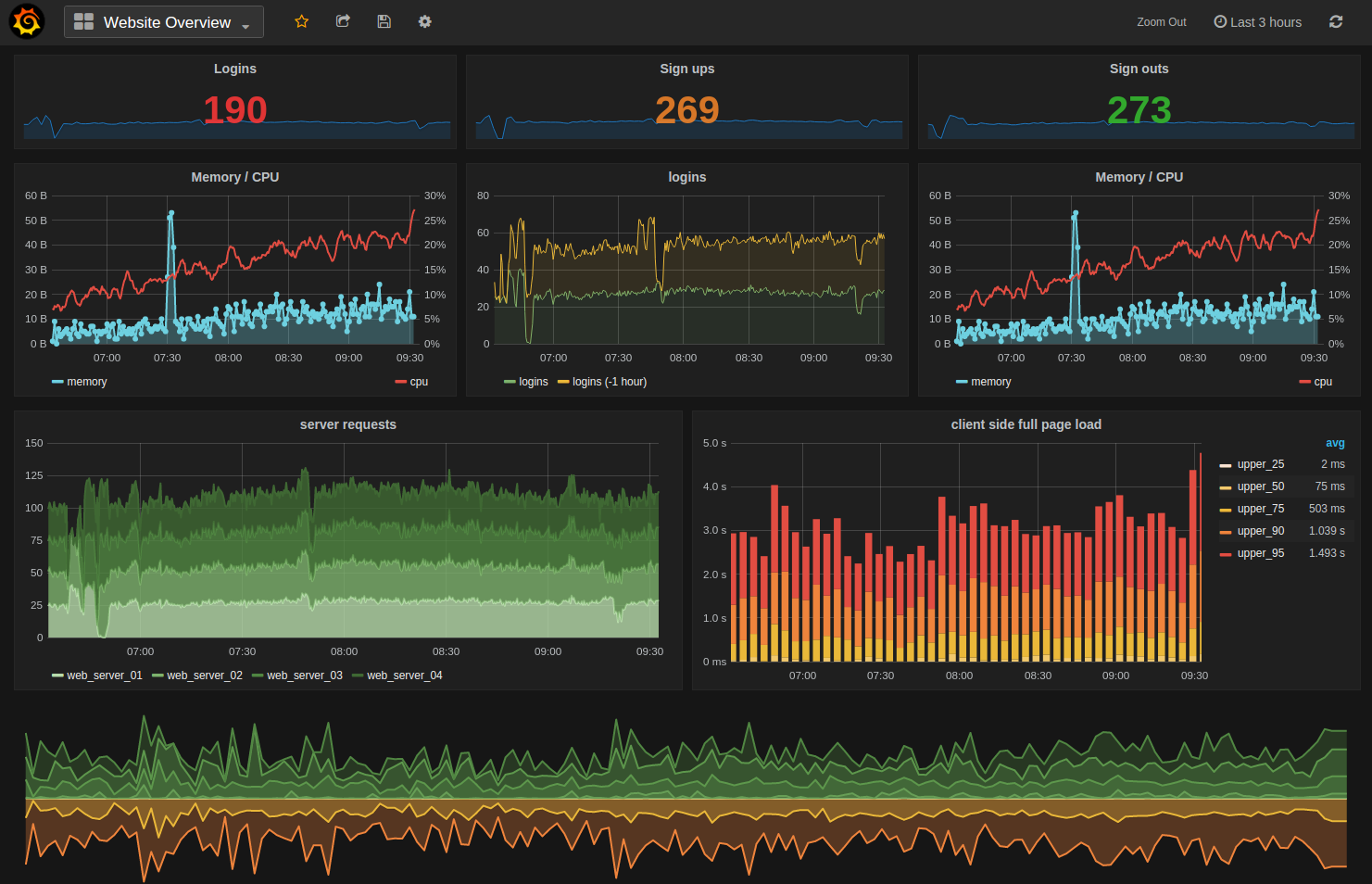

Hargo will also save its results to InfluxDB, if available. Each HTTP response is stored as a point of time-series data, which can be graphed by Chronograf, Grafana, or similar visualization tool for analysis.

Code Walkthrough

Hargo can be used as both a library and a cli tool. To use hargo as a library, simply import it:

import "github.com/mrichman/hargo"

To clone hargo locally, use git clone https://github.com/mrichman/hargo.git. Then cd hargo.

The main entry point to the cli is cmd/hargo/hargo.go.

Here, you’ll see I make use of the amazing github.com/urfave/cli package (formerly, github.com/codegangsta/cli). This package enables the construction of powerful cli apps in Go. This isn’t meant to be a tutorial on the cli package, but I’ll point out a few noteworthy lines of code:

Here, I set up the hargo fetch command, which takes as an argument the path to a .har file.

Note the use of newReader(). While I could have simply created buf := bufio.NewReader(file) here, there’s a peculiarity of some .har files I had to deal with. I noticed that some Windows-based tools like to completely ignore the spec and save in UTF-8 with the dreaded BOM (byte-order mark). Telerik Fiddler, an otherwise great tool, is one such program I’ve found to save .har files this way.

Since Go explicitly fails to decode JSON files with a BOM, I had to work around it. The key is to detect the BOM, and then remove the first 3 characters from the stream:

Now, if you have to work with .har files exported by Fiddler, or another noncompliant Windows-based tool, you’re all set.

Load Testing

Next, let’s take a look at Hargo’s load testing subcommand, load. We invoke the load test as follows:

hargo.LoadTest(r, workers, time.Duration(duration)*time.Second, *u)

The parameters are:

- r: the reader used to read the .har file

- workers: the number of concurrent worker routines (default 10)

- duration of the load test in seconds (default 60)

- u: the InfluxDB URL in which to store test result data

Now, we’ll explore the hargo.LoadTest() function:

You will notice I reference InfluxDB:

c, err := NewInfluxDBClient(u)

InfluxDB is a time-series database which can be (optionally) used to store the results of tests. In conjunction with InfluxDB, a tool like Grafana can visualize the test data like this:

If you don’t have InfluxDB installed, Hargo will simply ignore it when it fails to connect on startup.

Notice I use a WaitGroup, which is a synchronization primitive in Go I’m using in conjunction with the goroutine processEntries(). This construct allows me spin up any number of concurrent workers, and wait for them all to terminate before continuing. I also use a timeout to proceed after a specified duration, even if the workers have not yet completed:

The processEntries() function iterates through each Entry struct in the decoded .har file, and creates an HTTP request from it. With that request, I add the relevant cookies and HTTP headers.

Next, I execute the HTTP request using Client.Do(). With the HTTP response in hand, I can compute the latency of the response, and store the result:

I batch up these test results, and store them in InfluxDB for later visualization.

Watch it Go (pun intended)

So, now that you have an idea of how Hargo is constructed, let’s give it a whirl. We start by capturing a .har file using any tool that can perform such a feat. The easiest way for me is using Google Chrome. You can record these files by following the steps below:

- Right-click anywhere on that page and click on Inspect Element to open Chrome’s Developer Tools

- The Developer Tools will open as a panel at the bottom of the page. Click on the Network tab.

- Click the Record button, which is the solid black circle at the bottom of the Network tab, and you’ll start recording activity in your browser.

- Refresh the page and start working normally

- Right-click within the Network tab and click Save as HAR with Content to save a copy of the activity that you recorded.

- Within the file window, save the HAR file.

I captured a .har file using the Wikipedia article for .har files and saved it as en.wikipedia.org.har.

With your .har file saved, you can now execute a test:

hargo load en.wikipedia.org.har

And you’ll see some output

INFO[0000] load test .har file: en.wikipedia.org.har

INFO[0000] Connecting to InfluxDB: http://localhost:8086/hargo

INFO[0000] DB: hargo

INFO[0000] Recording results to InfluxDB: http://localhost:8086/hargo

INFO[0000] Starting load test with 10 workers. Duration 1m0s.

After 60 seconds, the test completes. If you have InfluxDB installed, you can query the raw time-series data using the hargo database:

select * from test_result order by time desc limit 1000

InfluxDB Hargo Test Results

Each HTTP response is stored as a point of time-series data, which can be graphed by Chronograf, Grafana, or similar visualization tool for analysis.

Conclusion

Hargo is my latest performance testing workflow tool, written in Go. It lacks many features in commercial load testing tools, but I plan to expand on it, with feedback from the community. If you find any bugs, please report them! I am also happy to accept pull requests from anyone.

You can use the GitHub issue tracker to report bugs, ask questions, or suggest new features.

For a more informal setting to discuss this project, you can join the Gitter chat.